Lenin and Trotsky with Delegates of the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party

Wars of intervention did not begin with Iraq in 2003. In 1918, shortly after the Russian Revolution armies from 14 countries were sent to support right-wing and monarchist forces fighting to overthrow the Bolsheviks.

The revolutionary government’s withdrawal from World War One inspired soldiers on all sides and frightened Britain and its allies. Initial pro-war sentiment among workers was being replaced by hostility to the conflict and strikes.

In June 1917, following the overthrow of the Tsar, over 1,100 delegates met in Leeds and agreed to form a Council of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Delegates modelled on the lines of the Soviets that had been launched in Russia.

The foreign armies were eventually defeated by the newly-created Red Army but only after provoking a debilitating civil war. In spite of short-lived revolutions in Germany and Hungary and uprisings elsewhere, the new Soviet revolution remained isolated and surrounded by a hostile capitalist world.

Attempts to discredit the Russian Revolution often take the form of accusing the Bolshevik Party of being anti-democratic in essence, of containing within it from the outset, the seeds of bureaucracy, careerism and betrayal of the masses. Stalinism, in other words, is seen as the natural and inevitable outcome of an anti-democratic revolution and the way it was organised.

The reality is quite the opposite. The Bolshevik Party won the control of the majority of the 800 Soviets (local councils elected democratically) during the nine months between the two revolutions of 1917 as a result of its popular policies of Peace, Bread and Land.

There were plenty of divisions within the people, and plenty of different parties vying for leadership of the Soviets (the leaders of the print unions for instance supported the reformist Menshevik Party, the peasants were, by and large, members of the Socialist Revolutionary Party.

It was, of course, the workers who occupied the key buildings in Petrograd on November 7, finally storming the Winter Palace – where the Provisional Government which was continuing the war was holed up – making the revolution, an almost casualty-free event. The second All-Russian Congress of Soviets came together and handed power over to the Soviet Council of People’s Commissars. Lenin was elected chairman.

Two decrees were immediately adopted: one authorising the start of negotiations with Germany to end the war; and the other, to transfer land from landowners and the church over to peasant committees. Banks were nationalised and factory committees set up.

The new social order thus came about through democratic means. It could not have happened spontaneously, without the party, and without the ideas and the theory developed over decades, and the co-ordination, control and discipline that came from it. And of course it could not have happened without the active participation of the workers, the actual force for change.

Lenin speaks to soldiers

Lenin championed self-determination. In December 1917 the Bolsheviks recognised the Ukrainian republic. Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan also proclaimed their independence from Russia.

Subsequently, as the struggle to defend the revolution became more and more desperate, some of the democratic forms which had helped to drive the revolution, were suspended under the exigencies of “War Communism”. Under these measures a large part of the grain harvest was requisitioned to feed the people of the towns; the government took control of the railways to transport the army to the war theatres.

Food was rationed, strikes were outlawed and several other measures to increase the centralisation and the efficient management of the state in a time of war, were introduced. Similar measures existed in capitalist countries like Britain.

These emergency measures were made to unite the people against the marauding White Russian armies and their foreign backers. It was always the intention of the leaders of the Bolshevik Party to restore them – greater democracy and workers’ control had always been an essential ingredient of the revolution.

As the isolation of the new Soviet state and the shortages of everything within it multiplied, so did the difficulties. Although the economy had begun to recover by 1921, with industrial production increasing, it was still well below the levels of 1917 and incomparably lower than that in the advanced countries of the West. There was a two-year drought in large parts of the country and a catastrophic famine struck in 1921.

There were many peasant uprisings against the Bolsheviks, but there were also strikes in Petrograd and there was even a very threatening rebellion by sailors, soldiers and communists, centred in the naval base of Kronstadt in 1921, which shocked Lenin and Trotsky.

The introduction of the New Economic Policy in 1921 placated the richer peasants or kulaks, but also gave them greater bargaining power. The struggle against privilege, inequality and bureaucracy was joined in earnest at the top of the party itself.

Lenin clashed with Stalin more than once before his death in 1924, over his rudeness and his anti-democratic methods. In his last testament, written at the end of 1922, he called for the removal of Stalin from the position of general secretary of the party’s central committee. He also clashed with Stalin and others in defence of the right of the nations of the former Tsarist empire to self-determination.

Shortages and privations, together with the numerical weakness of the working class, its exhaustion and the failure to spread revolution to other countries were all factors in creating the conditions for the rise of a self-seeking privileged bureaucracy.

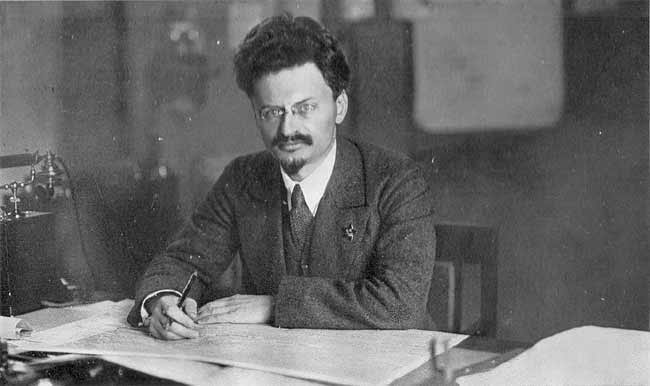

Trotsky in 1919

Over the next years the task of defending the principles of the party against all kinds of attacks and threats from Stalin who remained as general secretary and who controlled the party machine, fell to the Left Opposition led by Trotsky.

The Left Opposition drew up a platform of demands and presented them to a joint meeting of the central committee and the central control commission in 1926. The platform called for: the restoration of inner-party democracy; an increase in wages for industrial workers; freedom for the trade unions to negotiate wage claims; tax relief for the poor to put more of the burden back onto the kulaks and the rich; voluntary collectivisation with state credits for mechanisation; compulsory grain loans and a 50% tax on the profits of the kulaks; acceleration of industrialisation by implementing the decisions of the 14th Congress and the drawing up of a realistic five-year plan.

Stalin’s position appeared precarious. But this was a period of set-backs for the international working class. The 1923 revolution in Germany had been defeated; the 1926 general strike in Britain had been sold out by the trade union leaders; in 1927 thousands of members of the Chinese Communist Party were massacred.

Revolution was in retreat and Stalin’s “theory” of building socialism in a single country rationalised the position of the bureaucracy. Stalin could not allow the platform to be presented to the full 15th Party Congress. The Left Opposition managed to print their joint platform, but an agent in their ranks betrayed them and the duplicator and copies were seized. Discussion was stifled; expulsions from the party and notices of exile followed.

Trotsky himself was exiled and then deported. The inner-party struggle had apparently ended with Stalin’s victory. By 1938 not only had the ideas that inspired the revolution been largely smashed but the people who held them became victims of horrific purges and show trials which also decapitated the Red Army leadership just as a new world war beckoned.

The Communist parties of the world that were set up and grew through the 1920s, with the prestige of revolutionary Russia behind them, became, in practice, forces for counter-revolution. In the Spanish Civil War 1936-38, the Communist Party joined the bourgeois parties in the Popular Front government and then turned on the POUM, a coalition of forces fighting the Franco rebellion, with Trotskyists and anarchists at the head.

The POUM was outlawed, their leaders arrested, together with anyone who challenged the authority of the CP. Their leader, Andreas Nin, was tortured, denounced as a fascist and executed. George Orwell, author of 1984 and Animal Farm, narrowly escaped a similar fate after being tipped off before he was arrested.

Clearly we have to learn from the experiences of the Russian Revolution and its history. Opposing bureaucratic control wherever it appears is essential. Defending democratic rights is beyond question. Any idea of building socialism in one country ought to be scorned.

We should, in my view, defend the revolution itself as legitimate and a practice that has forced itself back on the agenda 100 years later.

Today the world economy is far more integrated and inter-dependant than in 1917. It is the nightmare of ruling elites everywhere that any single economy, whether in Greece, Italy or the UK, might fail, causing a world-wide seizure, and opening the way for a revolutionary situation – not just in a single country, but everywhere.

Globalisation, driven by the corporations, may have increased the scope and the profits of these outfits, but it has also led to a global weakness, the possibility that the breaking of a weak link could lead to a global crash.

The models for a new kind of society with new forms of participative democracy, with an economy that works for the many rather than just making profits for the few, with co-operative type economies, with realistic solutions for allowing the planet to recover from 200 years of abuse by capitalism, with a plan for world co-operation, and with practical solutions for combating poverty and inequality and for liberating the people – are all out there.

They are being considered and discussed by social movements and new campaigning organisations. Bringing them together in a co-ordinated way with the aim of making a transition beyond capitalism through a democratic revolution that transfers power to the 99% is not only possible but entirely necessary. It would be a fitting way to mark the anniversary of the Russian Revolution.